Nazi Propaganda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

''

''

Until the conclusion of the

Until the conclusion of the  On 23 June 1944, the Nazis permitted the

On 23 June 1944, the Nazis permitted the

The Nazis produced many films to promote their views, using the party's Department of Film for organizing film propaganda. An estimated 45 million people attended film screenings put on by the NSDAP. Reichsamtsleiter Neumann declared that the goal of the Department of Film was not directly political in nature, but was rather to influence the culture, education, and entertainment of the general population.

On 22 September 1933, a Department of Film was incorporated into the Chamber of Culture. The department controlled the licensing of every film prior to its production. Sometimes the government selected the actors for a film, financed the production partially or totally, and granted tax breaks to the producers. Awards for "valuable" films would decrease taxes, thus encouraging self-censorship among movie makers.

Under Goebbels and Hitler, the

The Nazis produced many films to promote their views, using the party's Department of Film for organizing film propaganda. An estimated 45 million people attended film screenings put on by the NSDAP. Reichsamtsleiter Neumann declared that the goal of the Department of Film was not directly political in nature, but was rather to influence the culture, education, and entertainment of the general population.

On 22 September 1933, a Department of Film was incorporated into the Chamber of Culture. The department controlled the licensing of every film prior to its production. Sometimes the government selected the actors for a film, financed the production partially or totally, and granted tax breaks to the producers. Awards for "valuable" films would decrease taxes, thus encouraging self-censorship among movie makers.

Under Goebbels and Hitler, the

By Nazi standards, fine art was not propaganda. Its purpose was to create ideals, for eternity. This produced a call for heroic and romantic art, which reflected the ideal rather than the realistic. Explicitly political paintings were very rare. Still more rare were antisemitic paintings, because the art was supposed to be on a higher plane. Nevertheless, selected themes, common in propaganda, were the most common topics of art.

Sculpture was used as an expression of Nazi racial theories. The most common image was of the nude male, expressing the ideal of the Aryan race. Nudes were required to be physically perfect.

By Nazi standards, fine art was not propaganda. Its purpose was to create ideals, for eternity. This produced a call for heroic and romantic art, which reflected the ideal rather than the realistic. Explicitly political paintings were very rare. Still more rare were antisemitic paintings, because the art was supposed to be on a higher plane. Nevertheless, selected themes, common in propaganda, were the most common topics of art.

Sculpture was used as an expression of Nazi racial theories. The most common image was of the nude male, expressing the ideal of the Aryan race. Nudes were required to be physically perfect.

Fascinating Fascism

' At the Paris Exposition of 1937,

The Nazis used photographers to document events and promote ideology. Photographers included

The Nazis used photographers to document events and promote ideology. Photographers included

As well as domestic broadcasts, the Nazi regime used radio to deliver its message to both occupied territories and enemy states. One of the main targets was the United Kingdom, to which

As well as domestic broadcasts, the Nazi regime used radio to deliver its message to both occupied territories and enemy states. One of the main targets was the United Kingdom, to which

Advertising Evil: Pro-Nazi Posters

– slideshow by ''Life magazine'' * Calvin University. German Propaganda Archive

Nazi and East German Propaganda Guide Page

German Propaganda Archive

Vica Nazi Propaganda Comics – Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

2010 German Exhibit Shows Mass Appeal Of Nazi Ideology

– audio report by ''NPR'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Nazi Propaganda Nazi propaganda, Propaganda in Germany World War II propaganda Antisemitic propaganda Propaganda by topic Race-related controversies in radio Anti-communist propaganda Propaganda by country, Germany, Nazi Anti-Americanism, Propaganda in Nazi Germany

The

The propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

used by the German Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's dictatorship of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi policies

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

.

Themes

Nazi propaganda promotedNazi ideology

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

by demonizing the enemies of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

, notably Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

, but also capitalists and intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

s. It promoted the values asserted by the Nazis, including heroic death, ''Führerprinzip

The (; German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and t ...

'' (leader principle), ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community",Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'' (people's community), ''Blut und Boden

Atrocity is a German heavy metal band from Ludwigsburg that formed in 1985.

History

First started in 1985 as Instigators and playing grindcore, Atrocity arose as a death metal band with their debut EP, ''Blue Blood'', in 1989, followed soon b ...

'' (blood and soil) and pride in the Germanic ''Herrenvolk'' (master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific concept in Nazism, Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of Race (classification of human beings), human racial hierarchy. Members wer ...

). Propaganda was also used to maintain the cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

around Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, and to promote campaigns for eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and the annexation of German-speaking areas. After the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Nazi propaganda vilified Germany's enemies, notably the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States, and in 1943 exhorted the population to total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

.

History

''Mein Kampf'' (1925)

Adolf Hitler devoted two chapters of his 1925 book ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'', itself a propaganda tool, to the study and practice of propaganda. He claimed to have learned the value of propaganda as a World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

infantryman exposed to very effective British and ineffectual German propaganda. The argument that Germany lost the war largely because of British propaganda efforts, expounded at length in ''Mein Kampf'', reflected then-common German nationalist claims. Although untrue – German propaganda during World War I was mostly more advanced than that of the British – it became the official truth of Nazi Germany thanks to its reception by Hitler.Welch, 11.

While dictating Mein Kampf, Hitler used the term Big lie

A big lie (german: große Lüge) is a gross distortion or misrepresentation of the truth, used especially as a propaganda technique. The German expression was coined by Adolf Hitler, when he dictated his book '' Mein Kampf'' (1925), to descri ...

(in German: große Lüge), to refer to the use of a lie so enormous that no one would believe that someone "could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously."

''Mein Kampf'' contains the blueprint of later Nazi propaganda efforts. Assessing his audience, Hitler writes in chapter VI:

Propaganda must always address itself to the broad masses of the people. (...) All propaganda must be presented in a popular form and must fix its intellectual level so as not to be above the heads of the least intellectual of those to whom it is directed. (...) The art of propaganda consists precisely in being able to awaken the imagination of the public through an appeal to their feelings, in finding the appropriate psychological form that will arrest the attention and appeal to the hearts of the national masses. The broad masses of the people are not made up of diplomats or professors of public jurisprudence nor simply of persons who are able to form reasoned judgment in given cases, but a vacillating crowd of human children who are constantly wavering between one idea and another. (...) The great majority of a nation is so feminine in its character and outlook that its thought and conduct are ruled by sentiment rather than by sober reasoning. This sentiment, however, is not complex, but simple and consistent. It is not highly differentiated, but has only the negative and positive notions of love and hatred, right and wrong, truth and falsehood.''Mein Kampf'' citations are from theAs to the methods to be employed, he explains:Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg (PG) is a Virtual volunteering, volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks." It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the ...-hoste

1939 English translation by James Murphy

/ref>

Propaganda must not investigate the truth objectively and, in so far as it is favorable to the other side, present it according to the theoretical rules of justice; yet it must present only that aspect of the truth which is favorable to its own side. (...) The receptive powers of the masses are very restricted, and their understanding is feeble. On the other hand, they quickly forget. Such being the case, all effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare essentials and those must be expressed as far as possible in stereotyped formulas. These slogans should be persistently repeated until the very last individual has come to grasp the idea that has been put forward. (...) Every change that is made in the subject of a propagandist message must always emphasize the same conclusion. The leading slogan must, of course, be illustrated in many ways and from several angles, but in the end one must always return to the assertion of the same formula.

Early Nazi Party (1919–1933)

Hitler put these ideas into practice with the reestablishment of the ''Völkischer Beobachter

The ''Völkischer Beobachter'' (; "'' Völkisch'' Observer") was the newspaper of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) from 25 December 1920. It first appeared weekly, then daily from 8 February 1923. For twenty-four years it formed part of the official pub ...

'', a newspaper published by the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

(NSDAP) from December 1920 onwards, whose circulation reached 26,175 in 1929. It was joined in 1927 by Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

's ''Der Angriff

''Der Angriff'' (in English "The Attack") is a discontinued German language newspaper founded in 1927 by the Berlin Gau of the Nazi Party. The last edition was published on 24 April 1945.

History

The newspaper was set up by Joseph Goebbels, wh ...

'', another unabashedly and crudely propagandistic paper.

During most of the Nazis' time in opposition, their means of propaganda remained limited. With little access to mass media, the party continued to rely heavily on Hitler and a few others speaking at public meetings until 1929. One study finds that the Weimar government's use of pro-government radio propaganda slowed Nazi growth. In April 1930, Hitler appointed Goebbels head of party propaganda. Goebbels, a former journalist and Nazi Party officer in Berlin, soon proved his skills. Among his first successes was the organization of riotous demonstrations that succeeded in having the American anti-war film ''All Quiet on the Western Front

''All Quiet on the Western Front'' (german: Im Westen nichts Neues, lit=Nothing New in the West) is a novel by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. The book describes the German soldiers' extreme physical and mental trauma du ...

'' banned in Germany.Welch, 14.

In power (1933–1939)

A major political and ideological cornerstone of Nazi policy was the unification of all ethnic Germans living outside the Reich's borders (e.g. inAustria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

) under one Greater Germany. In ''Mein Kampf'', Hitler denounced the pain and misery of ethnic Germans outside Germany, and declared the dream of a common fatherland for which all Germans must fight. Throughout ''Mein Kampf'', he pushed Germans worldwide to make the struggle for political power and independence their main focus, made official in the ''Heim ins Reich

The ''Heim ins Reich'' (; meaning "back home to the Reich") was a foreign policy pursued by Adolf Hitler before and during World War II, beginning in 1938. The aim of Hitler's initiative was to convince all ''Volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) wh ...

'' policy beginning in 1938.

On 13 March 1933, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

established a Ministry of Propaganda, appointing Joseph Goebbels as its Minister. Its goals were to establish enemies in the public mind: the external enemies which had imposed the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

on Germany, and internal enemies such as Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

, homosexuals, Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, and cultural trends including "degenerate art

Degenerate art (german: Entartete Kunst was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, ...

".

For months prior to the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in 1939, German newspapers and leaders had carried out a national and international propaganda campaign accusing Polish authorities of organizing or tolerating violent ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

of ethnic German

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

s living in Poland. On 22 August, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

told his generals:

The main part of this propaganda campaign was the false flag Operation Himmler

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

, which was designed to create the appearance of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

aggression against Germany, in order to justify the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

.

Research finds that the Nazis' use of radio propaganda helped it consolidate power and enroll more party members.

There are a variety of factors that increased the obedience of German soldiers in terms of following the Nazi orders that were given to them regarding Jews. Omer Bartov, a professor on subjects such as German Studies and European History, mentioned in his book, ''Hitler’s Army: Soldiers, Nazis, and War in the Third Reich'', how German soldiers were told information that influenced their actions. Bartov mentioned that General Lemelson, a corps commander, explained to his German troops regarding their actions toward Jews, "We want to bring back peace, calm and order to this land…" German leaders tried to make their soldiers believe that Jews were a threat to their society. Thus, German soldiers followed orders given to them and participated in the demonization and mass murders of Jews. In other words, German soldiers saw Jews as a group that was trying to infect and take over their homeland. Omer Bartov's description of Nazi Germany explains the intense discipline and unity that the soldiers had which played a role in their willingness to obey orders that were given to them. These feelings that German soldiers had toward Jews grew more and more as time went on as the German leaders kept pushing further for Jews to get out of their land as they wanted total annihilation of Jews.

Antisemitism

''

''Der Stürmer

''Der Stürmer'' (, literally "The Stormer / Attacker / Striker") was a weekly German tabloid-format newspaper published from 1923 to the end of the Second World War by Julius Streicher, the ''Gauleiter'' of Franconia, with brief suspensions ...

'', a Nazi propaganda newspaper published by Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

told Germans that Jews kidnapped small children before Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

because "Jews need the blood of a Christian child, maybe, to mix in with their Matzah." A version was published in Romania by Karl Leopold von Möller

Count, Karl von Möller AOL O (11 October 1876 – 21 February 1943) was an officer, journalist, author and politician from Banat. He was an enthusiastic supporter of Hitler's National Socialism. In 1932, he published the antisemitic newspape ...

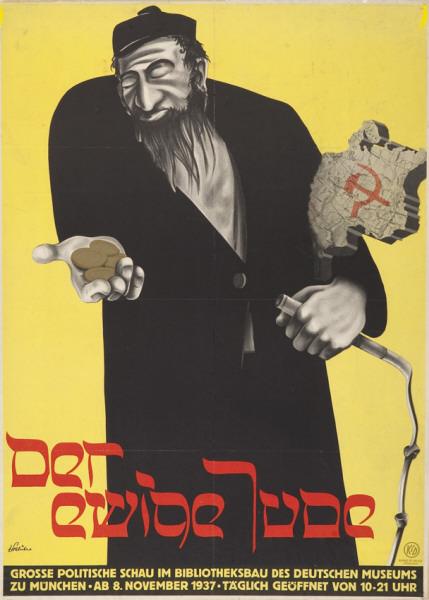

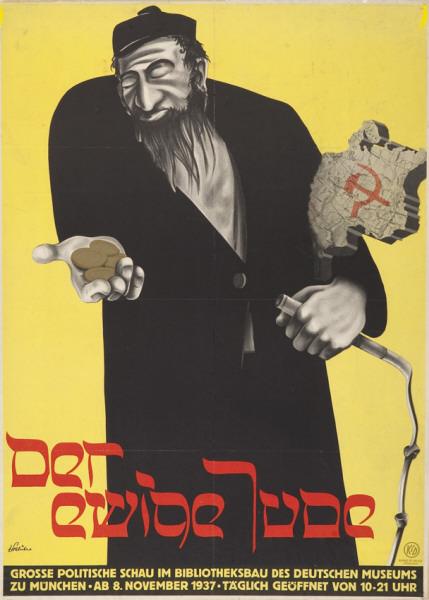

. Posters, films, cartoons, and fliers were seen throughout Germany which attacked the Jewish community. One of the most infamous such films was '' The Eternal Jew'' directed by Fritz Hippler

Fritz Hippler (17 August 1909 – 22 May 2002) was a German filmmaker who ran the film department in the Propaganda Ministry of Nazi Germany, under Joseph Goebbels. He is best known as the director of the propaganda film '' Der Ewige Jude (The ...

.

A study finds that the Nazis' use of radio propaganda incited antisemitic acts. Nazi radio was most effective in places where antisemitism was historically high but had a negative effect in places with historically low antisemitism.

Adolf Hitler and Nazi propagandists played on widespread and long-established German antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. The Jews were blamed for things such as robbing the German people of their hard work while themselves avoiding physical labour. Hitler declared that the mission of the Nazi movement was to annihilate "Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

", which was also called "Cultural Bolshevism

Degenerate art (german: Entartete Kunst was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, ...

". Hitler asserted that the "three vices" of " Jewish Marxism" were democracy, pacifism, and internationalism, and that the Jews were responsible for Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

, communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, and Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

. Joseph Goebbels in 1937 The Great Anti-Bolshevist Exhibition declared that Bolshevism and Jewry were one and the same.

At the 1935 Nazi Party congress rally at Nuremberg, Goebbels declared that "Bolshevism is the declaration of war by Jewish-led international subhumans against culture itself."

Euthanasia

The Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring was introduced on 14 July 1933, and various propaganda was used to target the disabled. A specialeuthanasia

Euthanasia (from el, εὐθανασία 'good death': εὖ, ''eu'' 'well, good' + θάνατος, ''thanatos'' 'death') is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different eut ...

program, called Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of ...

began in 1939, related propaganda arguments were based on the books, ''Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens'' ("Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living"), written by Karl Binding

Karl Ludwig Lorenz Binding (4 June 1841 – 7 April 1920) was a German jurist known as a promoter of the theory of retributive justice. His influential book, ''Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens'' ("Allowing the Destruction of Life ...

and Alfred Hoche

Alfred Erich Hoche (; 1 August 1865 – 16 May 1943) was a German psychiatrist known for his writings about eugenics and euthanasia.

Life

Hoche studied in Berlin and Heidelberg and became a psychiatrist in 1890. He moved to Strasbourg in 1891. ...

and the book ''Human Heredity Theory and Racial Hygiene'', written by Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 – 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, and a member of the Nazi Party. He served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, ...

, Erwin Baur Erwin Baur (16 April 1875, in Neuried, Ichenheim, Grand Duchy of Baden – 2 December 1933) was a German geneticist and botanist. Baur worked primarily on plant genetics. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Breeding Research (since 1 ...

and Fritz Lenz Fritz Gottlieb Karl Lenz (9 March 1887 in Pflugrade, Pomerania – 6 July 1976 in Göttingen, Lower Saxony) was a German geneticist, member of the Nazi Party,Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

, the laws excluded non-Aryans and political opponents of the Nazis from the civil-service and any sexual relations and marriage between people classified as "Aryan" and "non-Aryan" (Jews, Romani, Blacks) was prohibited as ''Rassenschande

''Rassenschande'' (, "racial shame") or ''Blutschande'' ( "blood disgrace") was an anti-miscegenation concept in Nazi German racial policy, pertaining to sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans. It was put into practice by policies like ...

'' or "race defilement". The Nuremberg Laws were based on notions of racial purity and sought to preserve the Aryan race, who were at the top of the Nazi racial hierarchy and were said to be the Übermenschen "Herrenvolk" (master race), and to teach the German nation to view the Jews as subhumans.

Working Class

TheStrength Through Joy

NC Gemeinschaft (KdF; ) was a German state-operated leisure organization in Nazi Germany.Richard Grunberger, ''The 12-Year Reich'', p. 197, It was part of the German Labour Front (german: link=no, Deutsche Arbeitsfront), the national labour org ...

(KdF) program was created to monitor what workers were doing in their non-working time. This was done to ensure that no German worker would be doing anything remotely involved with activities against the state. The KdF also monitored holidays and all leisure time by scheduling activities for workers so the workers would be happy and grateful for the activities and events/holidays that were given to them by the state. This produced support for the state from the working class which led to Nazi Germany's further rise in power. The KdF required members to participate in the activities offered to them, otherwise, any members who didn't participate were classified as anti-government. The classification of the said member would result in them being sent to a concentration camp as punishment. Robert Ley was head of the KdF and had a staff of roughly 7,000 working for the KdF and 30 million members prior to its dissolution in 1939 due to WWII.

Political opponents

Soon after the takeover of power in 1933,Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

were established for political opponents. The first people that were sent to the camps were political opponents, especially communists and socialists. They were sent because of their ties with the Soviet Union and because Nazism greatly opposed communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

. Nazi propaganda dismissed the Communists as "Red subhumans".

Goebbels used the death of the Nazi Party's Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; literally "Storm Detachment") was the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its primary purposes were providing protection for Nazi ral ...

(SA) Berlin leader Horst Wessel

Horst Ludwig Georg Erich Wessel (9 October 1907 – 23 February 1930) was a Berlin ''Sturmführer'' ("Assault Leader", the lowest commissioned officer rank) of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA), the Nazi Party's stormtroopers. After his killing in 1 ...

who was killed in 1930 by two members of the Communist Party of Germany as a propaganda tool for the Nazis against "Communist subhumans".

Treaty of Versailles

When theTreaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

was signed in 1919, non-propagandists newspapers headlines across the nation spoke German's feelings, such as ''"Schändlich!"'' ("Shameful!") which appeared on the front page of the ''Frankfurter Zeitung'' in 1919. The ''Berliner Tageblatt'', also in 1919, predicted: "Should we accept the conditions, a military furor for revenge will sound in Germany within a few years, a militant nationalism will engulf all." Hitler, knowing his nation's disgust with the Treaty, used it as leverage to influence his audience. He would repeatedly refer back to the terms of the Treaty as a direct attack on Germany and its people. In one speech delivered on 30 January 1937 he directly stated that he was withdrawing the German signature from the document to protest the outrageous proportions of the terms. He claimed the Treaty made Germany out to be inferior and "less" of a country than others only because blame for the war was placed on it. The success of Nazi propagandists and Hitler won the Nazi Party control of Germany and eventually led to World War II.

At war (1939–1945)

Until the conclusion of the

Until the conclusion of the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

on 2 February 1943, German propaganda emphasized the prowess of German arms and the humanity German soldiers had shown to the peoples of occupied territories. Pilots of the Allied bombing fleets were depicted as cowardly murderers and Americans in particular as gangsters in the style of Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the ...

. At the same time, German propaganda sought to alienate Americans and British from each other, and both these Western nations from the Soviet Union. One of the primary sources for propaganda was the Wehrmachtbericht

''Wehrmachtbericht'' (literally: "Armed forces report", usually translated as Wehrmacht communiqué or Wehrmacht report) was the daily Wehrmacht High Command mass-media communiqué and a key component of Nazi propaganda during World War II. Pr ...

, a daily radio broadcast from the High Command of the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

, the OKW. Nazi victories lent themselves easily to propaganda broadcasts and were at this point difficult to mishandle. Satires on the defeated, accounts of attacks, and praise for the fallen all were useful for Nazis. Still, failures were not easily handled even at this stage. For example, considerable embarrassment resulted when the ''Ark Royal'' proved to have survived an attack that German propaganda had hyped.

Goebbels instructed Nazi propagandists to describe the invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

) as the "European crusade against Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

" and the Nazis then formed different units of the Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

consisting of mainly volunteers and conscripts.

After Stalingrad, the main theme changed to Germany as the main defender of what they called "Western European culture" against the "Bolshevist hordes". The introduction of the V-1 V1, V01 or V-1 can refer to version one (for anything) (e.g., see version control)

V1, V01 or V-1 may also refer to:

In aircraft

* V-1 flying bomb, a World War II German weapon

* V1 speed, the maximum speed at which an aircraft pilot may abort ...

and V-2

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develope ...

"vengeance weapons" was emphasized to convince Britons of the hopelessness of defeating Germany.

On 23 June 1944, the Nazis permitted the

On 23 June 1944, the Nazis permitted the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

to visit the concentration camp Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination cam ...

to dispel rumors about the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

, which was intended to kill all Jews. In reality, Theresienstadt was a transit camp for Jews en route to extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s. In a sophisticated propaganda effort, fake shops and cafés were erected to imply that the Jews lived in relative comfort. The guests enjoyed the performance of a children's opera, '' Brundibar'', written by inmate Hans Krása

Hans Krása (30 November 1899 – 17 October 1944) was a Czech composer, murdered during the Holocaust at Auschwitz. He helped to organize cultural life in Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Life

Hans Krása was born in Prague, the son of Anna ...

. The hoax was so successful for the Nazis that they went on to make a propaganda film ''Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the Schutzstaffel, SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (German occupation of Czechoslovakia, German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstad ...

''. The shooting of the film began on 26 February 1944. Directed by Kurt Gerron

Kurt Gerron (11 May 1897 – 28 October 1944) was a German History of the Jews in Germany, Jewish actor and film director. He and his wife, Olga were murdered in the Holocaust.

Life

Born Kurt Gerson into a well-off merchant family in Berlin, he ...

, it was meant to show how well the Jews lived under the "benevolent" protection of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. After the shooting, most of the cast, and even the filmmaker himself, were deported to the concentration camp of Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

where they were murdered. Hans Fritzsche, who had been head of the Radio Chamber, was tried and acquitted by the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded ...

.

Antisemitism during World War II

Antisemitic wartime propaganda served a variety of purposes. It was hoped that people in Allied countries would be persuaded that Jews should be blamed for the war. The Nazis also wished to ensure that German people were aware of the extreme measures being carried out against the Jews on their behalf, in order to incriminate them and thus guarantee their continued loyalty through fear by Nazi-conjectured scenarios of supposed post-war "Jewish" reprisals. Especially from 1942 onwards, Nazi media vilified arch-enemies of Nazi Germany as Jewish (Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

) or in the cases of Josef Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

and Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

abject puppets of an international Jewish conspiracy intent on ruining Germany and Nazism.

Problems in propaganda arose easily in this stage; expectations of success were raised too high and too quickly, which required explanation if they were not fulfilled, and blunted the effects of success, and the hushing of blunders and failures caused mistrust. The increasing hardship of the war for the German people also called forth more propaganda that the war had been forced on the German people by the refusal of foreign powers to accept their strength and independence. Goebbels called for propaganda to toughen up the German people and not make victory look easy.

After Hitler's death

Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany#Nazi Germany (1933–1945), chancellor and dictator of Germany from 1933 to 1945, died by suicide via gunshot on 30 April 1945 in the in Berlin after it became clear that Germany would lose the Battle of B ...

, his successor as chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

, Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, informed the '' Reichssender Hamburg'' radio station. The station broke the initial news of Hitler's death on the night of 1 May; an announcer claimed he had died that afternoon as a hero fighting against Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

. Hitler's successor as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

, Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

, further asserted that the United States forces were continuing the war solely to spread Bolshevism, a Marxist-Leninist form of communism, within Europe.

Media

Books

The Nazis and sympathizers published many propaganda books. Most of the beliefs that would become associated with the Nazis, such as German nationalism,eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

had been in circulation since the 19th century, and the Nazis seized on this body of existing work in their own publications.

The most notable is Hitler's ''Mein Kampf'', detailing his beliefs. The book outlines major ideas that would later culminate in World War II. It is heavily influenced by Gustave Le Bon

Charles-Marie Gustave Le Bon (; 7 May 1841 – 13 December 1931) was a leading French polymath whose areas of interest included anthropology, psychology, sociology, medicine, invention, and physics. He is best known for his 1895 work '' The Crow ...

's 1895 ''The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind'', which theorized propaganda as a way to control the seemingly irrational behavior of crowds. Particularly prominent is the violent antisemitism of Hitler and his associates, drawing, among other sources, on the fabricated "Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

" (1897), which implied that Jews secretly conspired to rule the world. This book was a key source of propaganda for the Nazis and helped fuel their common hatred against the Jews during World War II. For example, Hitler claimed that the international language Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communi ...

was part of a Jewish plot and makes arguments toward the old German nationalist ideas of "Drang nach Osten

(; 'Drive to the East',Ulrich Best''Transgression as a Rule: German–Polish cross-border cooperation, border discourse and EU-enlargement'' 2008, p. 58, , Edmund Jan Osmańczyk, Anthony Mango, ''Encyclopedia of the United Nations and Interna ...

" and the necessity to gain Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

("living space") eastwards (especially in Russia).

Other books such as ''Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes

''Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes'' (English: ''Racial Science of the German People''), is a book written by German race researcher and Nazi Party member Hans Günther and published in 1922.Anne Maxwell. Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenic ...

'' ("Racial Science of the German People") by Hans Günther and ''Rasse und Seele'' ("Race and Soul") by Dr. (published under different titles between 1926 and 1934) attempt to identify and classify the differences between the German, Nordic, or Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

type and other supposedly inferior peoples. These books were used as texts in German schools during the Nazi era.

The pre-existing and popular genre of ''Schollen-roman'', or novel of the soil, also known as '' blood and soil'' novels, was given a boost by the acceptability of its themes to the Nazis and developed a mysticism of unity.

The immensely popular "Red Indian" stories by Karl May

Karl Friedrich May ( , ; 25 February 1842 – 30 March 1912) was a German author. He is best known for his 19th century novels of fictitious travels and adventures, set in the American Old West with Winnetou and Old Shatterhand as main pro ...

were permitted despite the heroic treatment of the hero Winnetou

Winnetou is a fictional Native American hero of several novels written in German by Karl May (1842–1912), one of the best-selling German writers of all time with about 200 million copies worldwide, including the ''Winnetou'' trilogy. The cha ...

and "colored" races; instead, the argument was made that the stories demonstrated the fall of the Red Indians was caused by a lack of racial consciousness, to encourage it in the Germans.Lynn H. Nicholas

Lynn H. Nicholas is the author of '' The Rape of Europa'', an account of Nazi plunder of looted art treasures from occupied countries. Her honors and awards include the Légion d'Honneur by France, Amicus Poloniae by Poland, and the National Book ...

, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 79 Other fictional works were also adapted; ''Heidi

''Heidi'' (; ) is a work of children's fiction published in 1881 by Swiss author Johanna Spyri, originally published in two parts as ''Heidi: Her Years of Wandering and Learning'' (german: Heidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre) and ''Heidi: How She Used ...

'' was stripped of its Christian elements, and Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

's relationship to Friday was made a master-slave one.

Children's books also made their appearance. In 1938, Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

published ''Der Giftpilz

''Der Giftpilz'' is a piece of antisemitic Nazi propaganda published as a children's book by Julius Streicher in 1938.antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

propaganda and stated that "The following tales tell the truth about the Jewish poison mushroom. They show the many shapes the Jew assumes. They show the depravity and baseness of the Jewish race. They show the Jew for what he really is: The Devil in human form."

Textbooks

"Geopolitical atlases" emphasized Nazi schemes, demonstrating the "encirclement" of Germany, depicting how the prolific Slav nations would cause the German people to be overrun, and (in contrast) showing the relative population density of Germany was much higher than that of the Eastern regions (where they would seekLebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

).Lynn H. Nicholas, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 76 Textbooks would often show that the birth rate amongst Slavs was prolific compared to Germans. Geography text books stated how crowded Germany had become. Other charts would show the cost of disabled children as opposed to healthy ones, or show how two-child families threatened the birthrate. Math books discussed military applications and used military word problems, physics and chemistry concentrated on military applications, and grammar classes were devoted to propaganda sentences. Other textbooks dealt with the history of the Nazi Party. Elementary school reading text included large amounts of propaganda. Children were taught through textbooks that they were the Aryan master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific concept in Nazism, Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of Race (classification of human beings), human racial hierarchy. Members wer ...

(''Herrenvolk'') while the Jews were untrustworthy, parasitic and ''Untermenschen

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non-Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

'' (inferior subhumans). Course content and textbooks unnecessarily included information that was propagandistic, an attempt to sway the children's views from an early age.

Maps showing the racial composition of Europe were banned from the classroom after many efforts that did not define the territory widely enough for party officials.

Fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic (paranormal), magic, incantation, enchantments, and mythical ...

s were put to use, with ''Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

'' being presented as a tale of how the prince's racial instincts lead him to reject the stepmother's alien blood (present in her daughters) for the racially pure maiden.Lynn H. Nicholas, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 77-8 Nordic sagas were likewise presented as the illustration of Führerprinzip

The (; German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and t ...

, which was developed with such heroes as Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

and Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

.Lynn H. Nicholas, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 78

Literature was to be chosen within the "German spirit" rather than a fixed list of forbidden and required, which made the teachers all the more cautious although Jewish authors were impossible for classrooms. While only William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' and ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' were actually recommended, none of the plays were actually forbidden, even ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', denounced for "flabbiness of soul."Milton Mayer, ''They Thought They Were Free: The Germans 1933–45'' p193 1995 University of Chicago Press Chicago

Biology texts, however, were put to the most use in presenting eugenic principles and racial theories; this included explanations of the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

, which were claimed to allow the German and Jewish peoples to co-exist without the danger of mixing.Lynn H. Nicholas, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 85 Science was to be presented as the most natural area for introducing the "Jewish Question" once teachers took care to point out that in nature, animals associated with those of their own species.

Teachers' guidelines on racial instruction presented both the handicapped and Jews as dangers. Despite their many photographs glamorizing the "Nordic" type, the texts also claimed that visual inspection was insufficient, and genealogical analysis was required to determine their types and report any hereditary problems.Lynn H. Nicholas, ''Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web'' p. 86 However, the National Socialist Teachers League

The National Socialist Teachers League (German: , NSLB), was established on 21 April 1929. Its original name was the Organization of National Socialist Educators. Its founder and first leader was former schoolteacher Hans Schemm, the Gauleiter ...

(NSLB) stressed that at primary schools, in particular, they had to work on only the Nordic racial core of the German ''Volk'' again and again and contrast it with the racial composition of foreign populations and the Jews.

Books for occupied countries

In occupied France, the German Institute encouraged the translation of German works although chiefly German nationalists, not ardent Nazis, produced a massive increase in the sale of translated works. The only books in English to be sold were English classics, and books with Jewish authors or Jewish subject matter (such as biographies) were banned, except for some scientific works. Control of the paper supply allowed Germans the easy ability to pressure publishers about books.Comics

The Nazi-controlled government in German-occupied France produced the ''Vica'' comic book series during World War II as a propaganda tool against the Allied forces. The Vica series, authored by Vincent Krassousky, represented Nazi influence and perspective in French society, and included such titles as ''Vica Contre le service secret Anglais'', and ''Vica défie l'Oncle Sam''.Films

The Nazis produced many films to promote their views, using the party's Department of Film for organizing film propaganda. An estimated 45 million people attended film screenings put on by the NSDAP. Reichsamtsleiter Neumann declared that the goal of the Department of Film was not directly political in nature, but was rather to influence the culture, education, and entertainment of the general population.

On 22 September 1933, a Department of Film was incorporated into the Chamber of Culture. The department controlled the licensing of every film prior to its production. Sometimes the government selected the actors for a film, financed the production partially or totally, and granted tax breaks to the producers. Awards for "valuable" films would decrease taxes, thus encouraging self-censorship among movie makers.

Under Goebbels and Hitler, the

The Nazis produced many films to promote their views, using the party's Department of Film for organizing film propaganda. An estimated 45 million people attended film screenings put on by the NSDAP. Reichsamtsleiter Neumann declared that the goal of the Department of Film was not directly political in nature, but was rather to influence the culture, education, and entertainment of the general population.

On 22 September 1933, a Department of Film was incorporated into the Chamber of Culture. The department controlled the licensing of every film prior to its production. Sometimes the government selected the actors for a film, financed the production partially or totally, and granted tax breaks to the producers. Awards for "valuable" films would decrease taxes, thus encouraging self-censorship among movie makers.

Under Goebbels and Hitler, the German film industry

The film industry in Germany can be traced back to the late 19th century. German cinema made major technical and artistic contributions to early film, broadcasting and television technology. Babelsberg Studio, Babelsberg became a household synon ...

became entirely nationalized. The National Socialist Propaganda Directorate, which Goebbels oversaw, had at its disposal nearly all film agencies in Germany by 1936. Occasionally, certain directors such as Wolfgang Liebeneiner

Wolfgang Georg Louis Liebeneiner (6 October 1905 – 28 November 1987) was a German actor, film director and theatre director.

Beginnings

He was born in Lubawka, Liebau in Prussian Silesia. In 1928, he was taught by Otto Falckenberg, the directo ...

were able to bypass Goebbels by providing him with a different version of the film than would be released. Such films include those directed by Helmut Käutner

Helmut Käutner (25 March 1908 – 20 April 1980) was a German film director active mainly in the 1940s and 1950s. He entered the film industry at the end of the Weimar Republic and released his first films as a director in Nazi Germany. Käu ...

: '' Romanze in Moll'' (''Romance in a Minor Key'', 1943), ''Große Freiheit Nr. 7

''Große Freiheit Nr. 7'' (English: ''Great Freedom No. 7'') is a 1944 German musical drama film directed by Helmut Käutner. It was named after Große Freiheit (grand freedom), a street next to Hamburg's Reeperbahn road in the St. Pauli red lig ...

'' (''The Great Freedom, No. 7'', 1944), and '' Unter den Brücken'' (''Under the Bridges'', 1945).

Schools were also provided with motion picture projectors because the film was regarded as particularly appropriate for propagandizing children.Anthony Rhodes, ''Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II'', p21 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York Films specifically created for schools were termed "military education."

''Triumph des Willens

''Triumph of the Will'' (german: Triumph des Willens) is a 1935 German Nazi propaganda film directed, produced, edited and co-written by Leni Riefenstahl. Adolf Hitler commissioned the film and served as an unofficial executive producer; his na ...

'' (''Triumph of the Will'', 1935) by film-maker Leni Riefenstahl

Helene Bertha Amalie "Leni" Riefenstahl (; 22 August 1902 – 8 September 2003) was a German film director, photographer and actress known for her role in producing Nazi propaganda.

A talented swimmer and an artist, Riefenstahl also became in ...

chronicled the Nazi Party Congress of 1934 in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

. It followed an earlier film of the 1933 Nuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg Rallies (officially ', meaning ''Reich Party Congress'') refer to a series of celebratory events coordinated by the Nazi Party in Germany. The first rally held took place in 1923. This rally was not particularly large or impactful; ...

produced by Riefenstahl, ''Der Sieg des Glaubens

''Der Sieg des Glaubens'' ( en, The Victory of Faith, Victory of Faith, or Victory of the Faith, italic=yes) is the first Nazi propaganda film directed by Leni Riefenstahl. Her film recounts the Fifth Party Rally of the Nazi Party, which occur ...

''. ''Triumph of the Will'' features footage of uniformed party members (though relatively few German soldiers), who are marching and drilling to militaristic

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

tunes. The film contains excerpts from speeches given by various Nazi leaders at the Congress, including Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. Frank Capra

Frank Russell Capra (born Francesco Rosario Capra; May 18, 1897 – September 3, 1991) was an Italian-born American film director, producer and writer who became the creative force behind some of the major award-winning films of the 1930s ...

used scenes from the film, which he described partially as "the ominous prelude of Hitler's holocaust of hate", in many parts of the United States government's ''Why We Fight

''Why We Fight'' is a series of seven propaganda films produced by the US Department of War from 1942 to 1945, during World War II. It was originally written for American soldiers to help them understand why the United States was involved in th ...

'' anti-Axis seven-film series, to demonstrate what the personnel of the American military would be facing in World War II, and why the Axis had to be defeated.

'' Der ewige Jude'' (''The Eternal Jew'', 1940) was directed by Fritz Hippler

Fritz Hippler (17 August 1909 – 22 May 2002) was a German filmmaker who ran the film department in the Propaganda Ministry of Nazi Germany, under Joseph Goebbels. He is best known as the director of the propaganda film '' Der Ewige Jude (The ...

at the insistence of Goebbels, though the writing is credited to Eberhard Taubert. The movie is done in the style of a feature-length documentary, the central thesis being the immutable racial personality traits that characterize the Jew as a wandering cultural parasite. Throughout the film, these traits are contrasted to the Nazi state ideal: while Aryan men find satisfaction in physical labour and the creation of value, Jews only find pleasure in money and a hedonist lifestyle. The movie is resolved with Hitler giving a speech hinting at the coming "Final Solution", his plan to exterminate millions of Jews. One historian has noted that "so radical was the film's antisemitism that the Propaganda Ministry had doubts about showing it to the public... it was most successful amongst Party activists; the general public was less impressed".

The main medium was Die Deutsche Wochenschau

''Die Deutsche Wochenschau'' (''The German Weekly Review'') was the title of the unified newsreel series released in the cinemas of Nazi Germany from June 1940 until the end of World War II. The coordinated newsreel production was set up as a vi ...

, a newsreel series produced for cinemas, from 1940. Newsreels were explicitly intended to portray German interests as successful.

Themes often included the virtues of the Nordic or Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

type, German military and industrial strength, and the evils of the Nazi enemies.

Fine art

By Nazi standards, fine art was not propaganda. Its purpose was to create ideals, for eternity. This produced a call for heroic and romantic art, which reflected the ideal rather than the realistic. Explicitly political paintings were very rare. Still more rare were antisemitic paintings, because the art was supposed to be on a higher plane. Nevertheless, selected themes, common in propaganda, were the most common topics of art.

Sculpture was used as an expression of Nazi racial theories. The most common image was of the nude male, expressing the ideal of the Aryan race. Nudes were required to be physically perfect.

By Nazi standards, fine art was not propaganda. Its purpose was to create ideals, for eternity. This produced a call for heroic and romantic art, which reflected the ideal rather than the realistic. Explicitly political paintings were very rare. Still more rare were antisemitic paintings, because the art was supposed to be on a higher plane. Nevertheless, selected themes, common in propaganda, were the most common topics of art.

Sculpture was used as an expression of Nazi racial theories. The most common image was of the nude male, expressing the ideal of the Aryan race. Nudes were required to be physically perfect.Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag (; January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) was an American writer, philosopher, and political activist. She mostly wrote essays, but also published novels; she published her first major work, the essay "Notes on 'Camp'", in 1964. Her ...

, Fascinating Fascism

' At the Paris Exposition of 1937,

Josef Thorak

Josef Thorak (7 February 1889 in Vienna, Austria – 26 February 1952 in Bad Endorf, Bavaria) was an Austrian-German sculptor. He became known for oversize monumental sculptures, particularly of male figures, and was one of the most promin ...

's ''Comradeship'' stood outside the German pavilion, depicting two enormous nude males, clasping hands and standing defiantly side by side, in a pose of defense and racial camaraderie.

Landscape painting

Landscape painting, also known as landscape art, is the depiction of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, especially where the main subject is a wide view—with its elements arranged into a coherent compos ...

featured mostly heavily in the Greater German Art exhibition, in accordance with themes of blood and soil. Peasants were also popular images, reflecting a simple life in harmony with nature, frequently with large families. With the advent of war, war art came to be a significant though still not predominating proportion.

The continuing of the German Art Exhibition throughout the war was put forth as a manifestation of German's culture.

Magazines

In and after 1939, the ''Zeitschriften-Dienst'' was sent to magazines to provide guidelines on what to write for appropriate topics. Nazi publications also carried various forms of propaganda. '' Neues Volk'' was a monthly publication of theOffice of Racial Policy

The Office of Racial Policy was a department of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that was founded for "unifying and supervising all indoctrination and propaganda work in the field of population and racial politics". It began in 1933 as the Nazi Party Offi ...

, which answered questions about acceptable race relations. While mainly focused on race relations, it also included articles about the strength and character of the Aryan race compared to Jews and other "defectives".

The ''NS-Frauen-Warte

The ''NS-Frauen-Warte'' ("National Socialist Women's Monitor") was the Nazi magazine for women. Put out by the NS-Frauenschaft, it had the status of the only party approved magazine for women and served propaganda purposes, particularly supporti ...

'', aimed at women, included such topics as the role of women in the Nazi state. Despite its propaganda elements, it was predominantly a women's magazine. Leila J. Rupp, ''Mobilizing Women for War'', p 45, , It defended anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, and science as impractical, politically ...

, urged women to have children, even in wartime, put forth what the Nazis had done for women, discussed bridal schools, and urged women to greater efforts in total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

.

''Der Pimpf

''Der Pimpf'' () was the Nazi magazine for boys, particularly those in the ''Deutsches Jungvolk'', with adventure and propaganda.Material from "Der Pimpf"' It first appeared in 1935 as ''Morgen'', changing its name to ''Der Pimpf'' in 1937; its p ...

'' was aimed at boys, and contained both adventure and propaganda.

'' Das deutsche Mädel'', in contrast, recommended that girls take up hiking, tending the wounded, and preparing to care for children. Far more than ''NS-Frauen-Warte'', it emphasized the strong and active German woman.

Signal

''Signal'' was a propaganda magazine published by theWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and distributed throughout occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

and neutral countries. Published from April 1940 to March 1945, "Signal" had the highest sales of any magazine published in Europe during the period—circulation peaked at 2.5 million in 1943. At various times, it was published in at least twenty languages. An English edition was distributed in the British Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

of Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label=Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependencies, Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west F ...

, Alderney